Remembering the Fallen Forests

It's the time of the year for remembering the dead. How can we begin to grieve the physical and spiritual loss of the forest?

I recently read “The Church Forests of Ethiopia: A Mystical Geography” by Fred Bahnson. The essay was recommended to me by my boss, since our program is in the midst of engaging in multi-year tree planting projects. The essay vividly tells about the isolated pockets of ancient forest that surround Ethiopian Orthodox churches, and how the church is preserving these sacred groves amidst rampant deforestation.

The piece got me thinking about the spiritual ramifications of deforestation where I live, in North America.

I don’t think about deforestation a lot. Maybe because I think a lot about other aspects of colonialism more—like the mass killings and the attempt at the erasure of culture of indigenous peoples. And maybe because a lot of North American deforestation happened before my lifetime. As someone living in the 21st century in a North American city, I think and feel like it’s normal to experience wide open plains, or cities with trees only near the streets. This has always been my reality.

I was recently in Theodore Wirth Park and was realizing that this park is special, in terms of having an urban forest in the middle of the city, but also that nearly the whole city used to be covered by forests. Old growth hardwood. And then that thousands and millions of those living beings were chopped down. Harvested to make a profit. I realized that while the forest provides a spiritual reprieve, the landscape used to be so much different…we didn’t need to drive across town to feel surrounded by trees and birdsong. Everywhere used to be forested. Everywhere used to be sacred.

I’ve been thinking about enchantment, and it’s reverse, disenchantment, a lot lately. By enchantment, I mean the act of seeing everything in the natural world as spiritual and wonderous. And by disenchantment, I mean the current common reality of seeing only our singular selves as spiritual and wonderous (and maybe seeing a church building on Sunday mornings between the hours of 10AM and 11AM as spiritual, and the preacher’s words as wonderous).

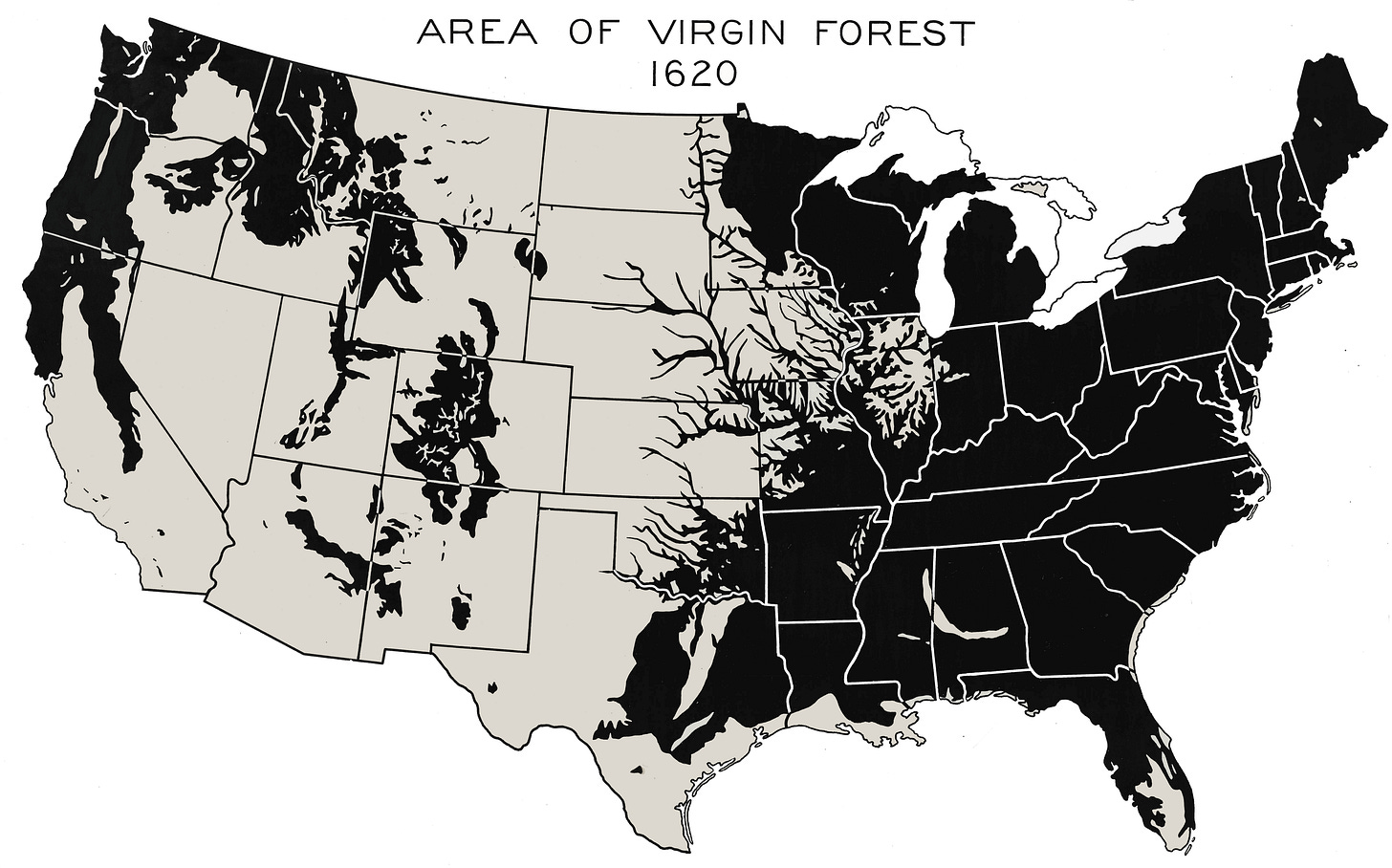

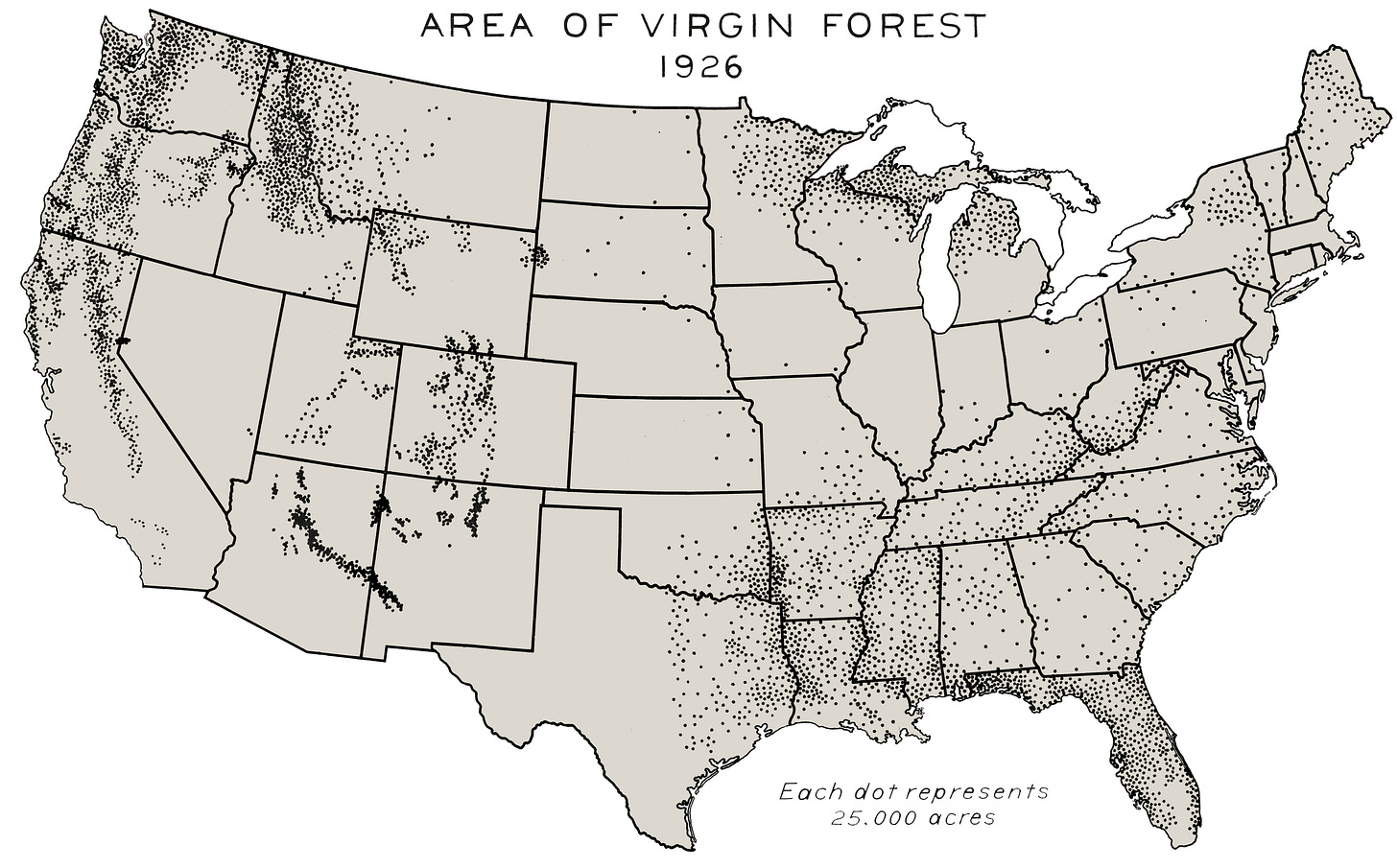

If the natural words is rendered disenchanted, it makes sense why deforestation happened—and not only passively happened, but how it was an economic priority. Europeans didn’t see the forest as sacred, which made it easy to deforest ninety percent of the forest cover. Now we have a double bind as modern day guests on the land—we don’t see nature as sacred, and there are very few places to experience it anyway. Life becomes about commuting on paved roads in boxes of metal hurling down said roads—roads that don’t even follow the river or natural landscape features—and sitting inside plastic squares inside of concrete cubes for eight hours a day, at least.

In Ecowomanism, Melanie Harris quotes Alice Walker, recalling an instance of witnessing a logging truck full of tree corpses, “the truck like a hearse”.

In many ways we are spiritually coping with the loss of 90% of our land’s trees. To say the word loss implies a passivity. Walker refers to the trees as kin, calling the logs “battered bodies of old sisters and brothers”. What has happened to the trees is more of a systematic murder, similar to the other mass deaths that were carried out on turtle island.

I wonder how much this has damaged our spirituality. I don’t think it’s quantifiable or understandable, but at the very least we must name that colonization has taken so much and killed so many.

We might talk about this simply as a loss, but it is also a powerful example of a collective sin.

How can we begin to repent of this collective sin?

It doesn’t seem enough to plant trees on church properties. But, maybe, it is a start. The “church forests” essay talks about the importance and power of a religious imagination. I suppose it’s one thing to imagine churches as plots of land that might become more shaded over the next few decades, making them slightly more resilient to extreme heat.

It’s another thing to imagine the extent of forests pre-colonization and how that shaped people’s spirituality, to imagine how the loss of that forest continues to shape our spirituality, and to realize how no matter how many new trees get in the ground in the next couple years, that we won’t be anywhere near restoring all that has been lost. There’s something about facing reality and grieving that expands our imagination, even if its painful, even if it makes us face all that we have lost.

Perhaps in an alternative timeline if colonization had still happened and we were facing down the numerous ecological crises of our times, yet in a twist of fate still had the forests, perhaps we’d be more resilient. Perhaps we’d be more equipped. Perhaps we would have internalized the spiritual lessons from trees.

But this is not our reality. Now we must work for repair amidst our concrete blocks, surrounded by paved roads, with a fragile, limited, and in some cases non-existent regard for the sacredness of nature….much less an internalization of the lessons from nature about how to be on this planet.

Bleak. This feels difficult, if not impossible.

I do believe that one day we will return back into relationship with the earth and each other. I don’t know much about what I believe about eschatology anymore, but I do believe in the earth as a balancing power, and that devastation will continue until we learn and relearn and remember how to be in reciprocal relationship. In that, I do take some hope, because if technocratic solutions to climate change were real and true and effective, then our societies would not have to change a bit about how we relate to earth and each other, and we would be able to find hope in false gods, false power, and false solutions. It truly would be enough to think about positive vibes and be more optimistic. It would actually be enough to electrify everything and not repair the harms of this country’s legacy of genocide, ecocide, and slavery. However, we still live in the natural world, an earth where cycles of death and rebirth are constant, and where relationship rules everything. So if there is to be a rebirth, there must be a reckoning with the death and with the grief.

In the meantime, I am grateful to have a forest right near my house, that was created in the early 1900s. The park was renamed after the parks superintendent, Theodore Wirth, a Swiss immigrant responsible for planning Minneapolis’s parks system, which many consider one of the best in the country. Yes, 44% of the state’s forests were removed from this land from 1870s to the 1930s, but at the very least there are small oases where residents can experience the enchantment of the forest, or the magic of the lakes, or the sacredness of the River, and for that I am grateful, because it continues to sustain me and draws me back into a relationship I am continually re-remembering.